Issue No. 22: World AMR Awareness Week 2023

The global community of scientists, doctors, researchers, and policymakers is in the midst of a weeklong event to tell the world about the dangers of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and what can be done about it. With this year’s World AMR Awareness Week(WAAW) in full swing, now is a great time to look at what’s been happening to fight the AMR crisis since last year’s WAAW.

The short answer: Lots has happened — some good and some bad. On the positive side, stakeholders around the world continue to work on ways to address the crisis, and the World Health Organization has outlined a new AMR research agenda. On the negative side, antimicrobial developers are still struggling to stay in business, and there have been several nationwide outbreaks of resistant, infectious bacteria and fungi in the United States.

But through it all, there’s hope that leaders around the globe will continue to work to devote resources to address the AMR crisis in the coming years. With the reintroduction of the PASTEUR Act to revamp the market for antimicrobial development, lawmakers in the United States may help set the course for a new generation of superbug-killers — if the legislation becomes law.

AMR Remains a Crisis

In epidemiological and medical terms, there’s been no relief from the AMR crisis in 2023. If anything, the dangerous consequences of drug-resistant superbugs hit close to home in cities all over the globe.

Superbugs kill hundreds of thousands of Americans every year, and contribute to millions of deaths around the world, because they resist known treatments. When patients take an antimicrobial, it kills most of the targeted infectious bacteria or fungi. But some survive and eventually evolve to resist the antimicrobials currently available. When a doctor sees a patient with such an infection and tries drug after drug to fight it without success, the patient’s life is at risk.

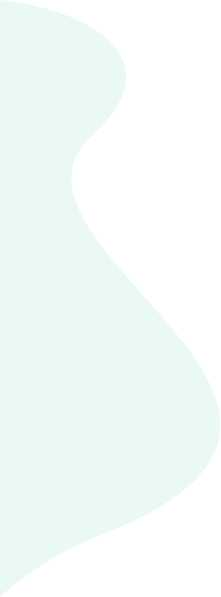

If researchers don’t develop new antimicrobials that can fight resistant strains of bacteria and fungi, by 2050, 10 million peopleworldwide may succumb to AMR infections every year, according to one widely cited report. In 2019, AMR contributed to nearly 173,000 deaths in the United States alone. This places AMR as the third leading cause of death from disease in the United States. Globally, a systematic analysis in The Lancet found bacterial AMR was associated with as many as 5 million deaths in 2019. AMR is not some hypothesized future crisis. It’s here now.

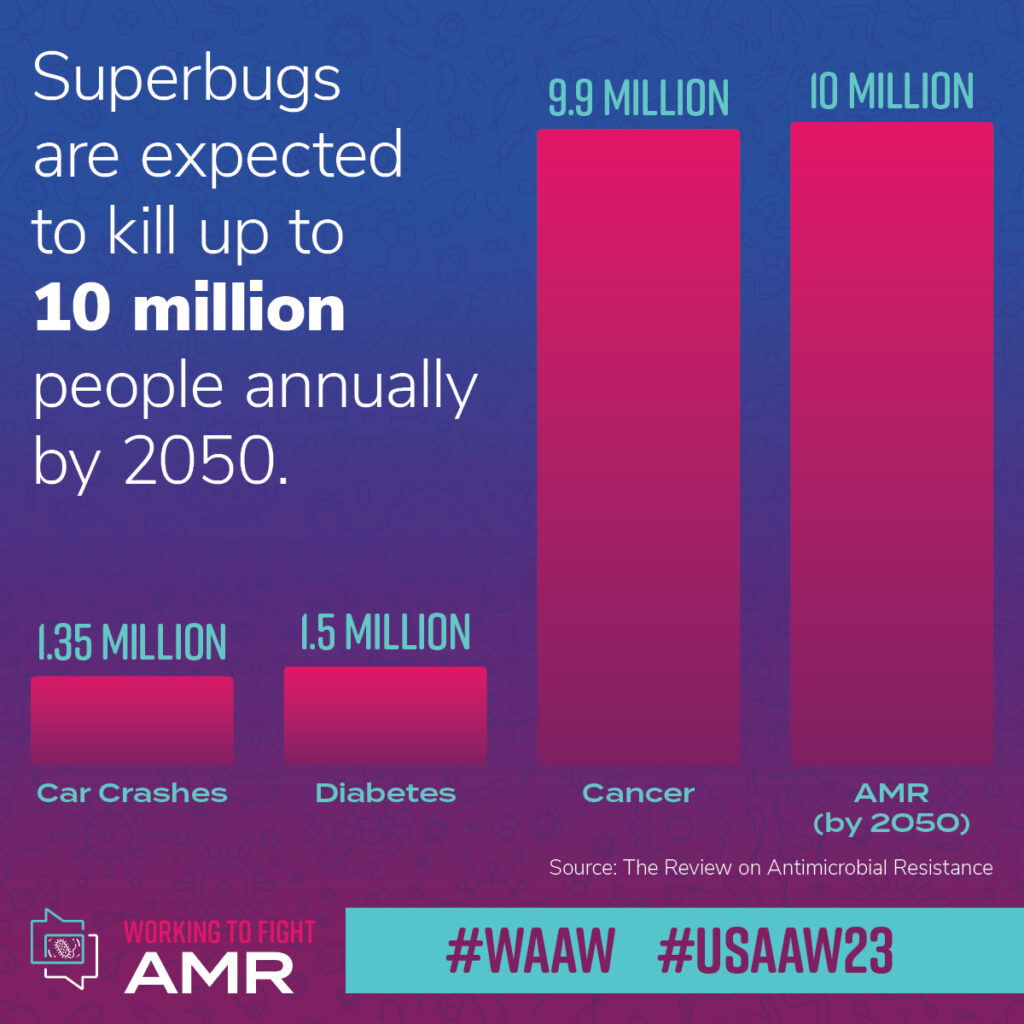

And it’s a crisis that played out in headlines across the United States in 2023. The prevalence of these superbugs is more apparent than ever before, as four pathogens resistant to antimicrobials garnered headlines this year.

Candida auris, a drug-resistant fungal infection that attacks the bloodstream and kills up to 60 percent of the people it infects, has been spreading since it was first discovered in the United States in 2016, as the Wall Street Journal reports. Since then, cases have risen every year — by 44 percent in 2019 and a staggering 95 percent in 2021. The CDC and WHO have put C. auris on their list of pathogens posing the greatest concern to human health.

Meanwhile, in March, the CDC warned the public of a highly drug-resistant strain of Shigella bacteria. The infection associated with it, shigellosis, can cause very unpleasant intestinal and digestive tract symptoms, including diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and severe stomach pain. Worryingly, this year’s outbreak was nothing new. Shigella infects approximately 450,000 Americans each year, with over 6,000 hospitalized as a result.

And at the start of 2023, a drug-resistant strain of gonorrhea, the sexually transmitted infection, wreaked havoc in Massachusetts. The bacteria either didn’t respond or had a reduced response to five different classes of antibiotics, making the strain a superbug.

New Global Research Priorities for AMR

As the crisis ramps up, so has the response from stakeholders. This June, the World Health Organization published a policy brief called “Global Research Agenda for Antimicrobial Resistance in Human Health.” The first-of-its-kind agenda focuses on WHO bacterial and fungal priority pathogens like Candida auris and identifies “the research topics with the greatest impact on mitigating antimicrobial resistance in the human health sector.”

In total, the WHO laid out 40 priorities grouped into five categories: Prevention, diagnosis and diagnostics, treatment and care, cross-cutting (epidemiology, burden, and drivers of AMR), and drug-resistant tuberculosis. Taken together, the WHO hopes its 40 priorities will lead to better policies and programs to address AMR.

A Broken Marketplace Puts Would-Be AMR Therapies in the Red

But while these initiatives are crucial, they’re not a silver bullet that would stop AMR on their own. That’s because drug developers that have attempted to create a new superbug-killer have either been acquired for pennies on the dollar or gone out of business soon after FDA approval. And it’s not because their treatments didn’t work. It’s because the economic model for new antimicrobial treatments is broken.

Because AMR pathogens can adapt and evolve, doctors prescribe antibiotics only when strictly necessary. They want to prevent the overuse and inappropriate use of antibiotics, both of which contribute to more resistance.

Ensuring new treatments are used appropriately — and judiciously — means the traditional economics of the prescription drug market don’t work for antimicrobials. Since new antimicrobial products must be used less frequently, antimicrobial innovators often struggle to earn a sustainable return on investment from volume alone. A new and different approach to the antimicrobial market — based on the critical value of these products to public health rather than volume — is needed.

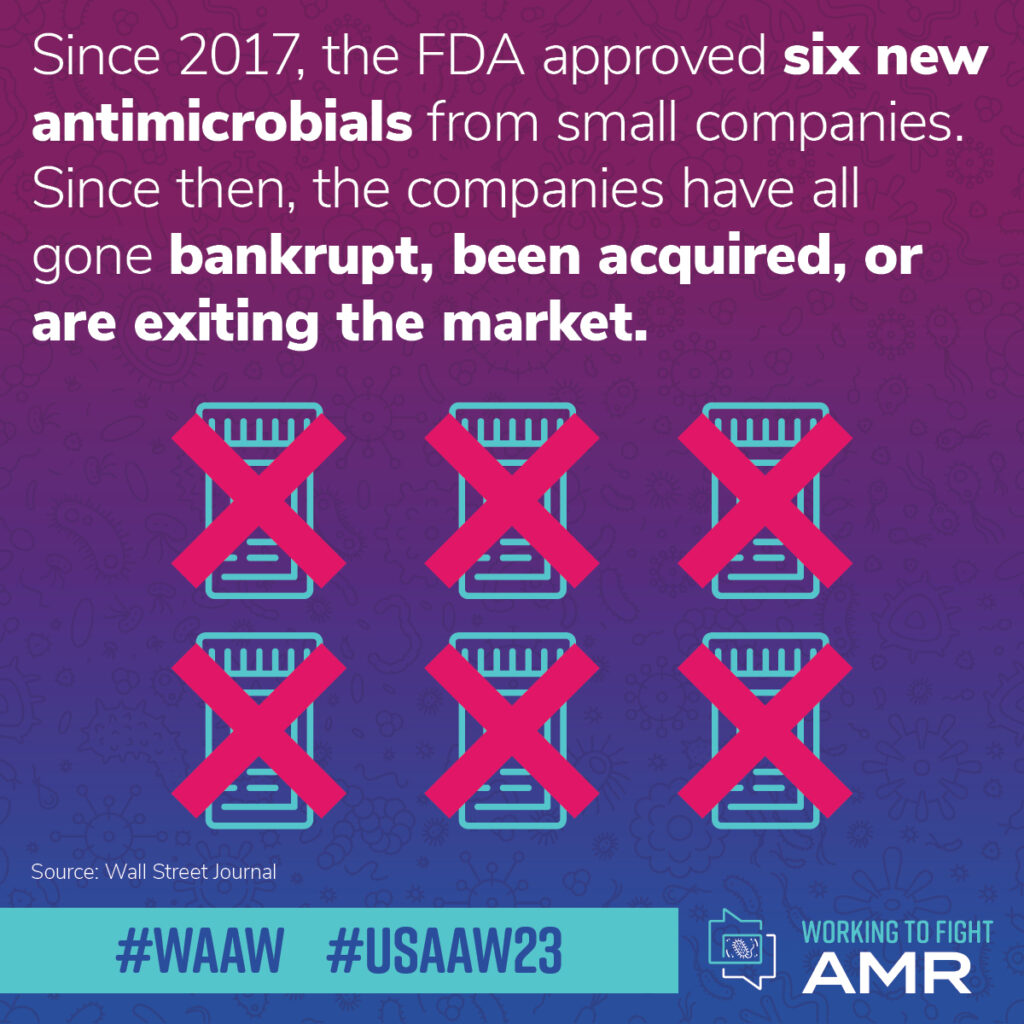

In recent years, several small companies have tried to sustain a business with a new antibiotic. All have failed to remain viable. The Wall Street Journal reports that six antimicrobials from small companies have received FDA approval since 2017. Since then, the companies have all filed for bankruptcy, been acquired, or are shutting down.

And it’s getting harder and harder to keep researchers and developers in the antimicrobial space. Kevin Outterson, executive director of CARB-X — a global non-profit partnership that supports the development of new antimicrobials — explained in the Wall Street Journal that around 80 percent of the 300 scientists who worked at companies that failed are no longer pursuing antibiotic development.

After the gonorrhea outbreak this year, Bloomberg reported new treatment development is underway to counter the resistant strains. NBC News also reported that a promising new antibiotic is being developed to attack gonorrhea infections in a new way and has proven to be effective against some resistant strains. But even if these companies succeed in gaining approval of these drugs, they still face the challenges of the current broken antimicrobial commercialization ecosystem.

Putting It All Together With PASTEUR

To support innovators working on new antimicrobials, lawmakers need to fix the fundamental flaw in the antimicrobials market. Fortunately, a policy solution is currently under consideration in Congress that would help antimicrobial developers keep their lights on and ensure their treatments remain commercially viable.

In April, a bipartisan group of senators and representatives reintroduced the PASTEUR Act, which would create a subscription-like mechanism for newly approved antimicrobials for federal health programs. First put forward in 2020, the law would allow the federal government to enter into contracts with innovators that develop new antibiotics that treat the most threatening infections or address unmet needs to ensure availability for patients under programs like Medicare. Under this novel payment mechanism, antibiotics would be sold based on the value of the product to patients and public health, rather than the volume or number of units sold.

Support for the PASTEUR Act has been growing steadily as awareness of the challenging antimicrobial market has increased. Over 230 groups — including pharmaceutical and medical trade associations, patient groups, and universities — sent a message to Congress urging passage of the PASTEUR Act urgently.

We know how to fight AMR. We have the science and there are policy solutions to help address it. As World AMR Awareness Week wraps up and we look to 2024, the time to act is now.

Click here to subscribe to the Superbug Bulletin.