Issue No. 21: Four Superbug Outbreaks Sound the Alarm about AMR

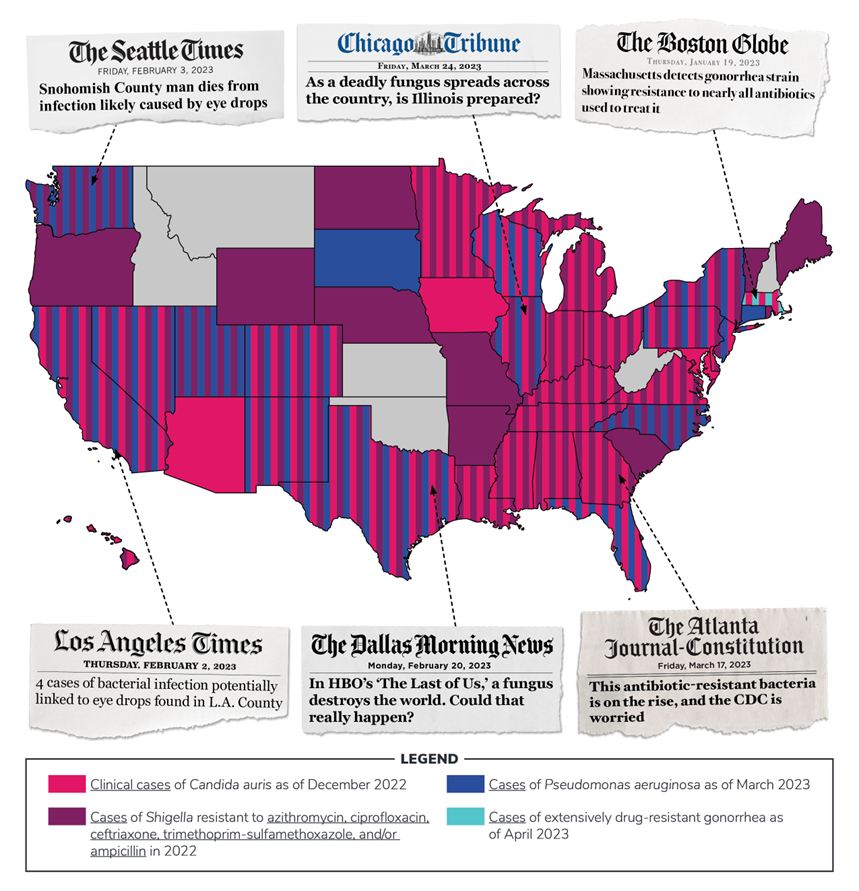

The crisis of drug-resistant “superbug” infections continues to escalate, as several recent U.S. outbreaks have made frighteningly clear. Over the past few months, four antimicrobial resistant (AMR) pathogens have been spreading at alarming rates: the fungus Candida auris, the sexually transmitted disease Gonorrhea, and the two bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Shigella.

These infections have added new urgency to the effort to develop novel and more powerful tools for beating back drug-resistant infections. Lawmakers in Washington have recognized the need for action on this front. In April, a bipartisan group in Congress reintroduced the Pioneering Antimicrobial Subscriptions to End Upsurging Resistance (PASTEUR) Act — a reform aimed at fostering the development of a new generation of antimicrobials.

If the healthcare community is to have any hope of overcoming the AMR crisis, policymakers in Washington must pass the PASTEUR Act quickly.

A Crisis Years in the Making

The catastrophic dangers posed by various superbugs have been well understood for years. But to date, efforts to neutralize this global public health threat have fallen woefully short. As recently as 2014, roughly 700,000 people around the world lost their lives to some form of an AMR infection. Just a few years later, a report in the British medical journal The Lancet estimated that bacterial superbugs alone were involved in the deaths of nearly 5 million patients in 2019.

At the time, there was reason to believe we were making progress to begin turning the page on the AMR threat. Then came Covid-19. As the pandemic pushed the world’s public health infrastructure to the breaking point, many strategies for combating AMR became compromised.

In particular, the widespread use of antibiotics during this period further aggravated the AMR crisis, giving a wide array of pathogens new opportunities to adapt and grow resistant to these medicines. As a result, 2020 saw a devastating 15 percent increase in both infections and deaths from hospital-onset AMR pathogens. And some resistant infections saw increases of over 70% over 2020.

Today, four superbug outbreaks, in particular, have raised concerns among U.S. public health officials. And without immediate action, the prospects for protecting patients from these infections will grow less and less promising by the day.

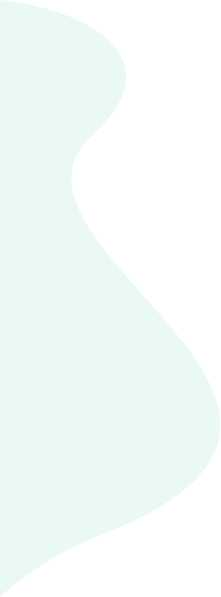

Candida auris Spreads Far and Fast

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and World Health Organization (WHO) have named the drug-resistant fungus Candida auris among the pathogens that pose the greatest threat to public health. Candida auris can affect patients of all ages, causing potentially fatal bloodstream infections that lead to fever, chills, and low blood pressure.

The first reported case of Candida auris in the United States dates to 2016. And, as a study published this April in the Annals of Internal Medicine finds, infection rates have skyrocketed since then. In its summary of that study, the CDC explains there have been “a total of 3,270 clinical cases (in which infection is present) and 7,413 screening cases (in which the fungus is detected but not causing infection) reported through December 31, 2021.”

Just as troubling is the astoundingly fast rate at which cases have increased in recent years. For instance, in 2019, clinical cases of Candida auris grew by 44 percent across the country. In 2021, however, cases rose at a rate more than twice as fast, 95 percent. The fungal infection has also been spreading across a larger and larger geographic area, with 17 states reporting their first cases of Candida auris between 2019 and 2021.

As with many drug-resistant infections, Candida auris is especially dangerous for patients with serious health conditions. It can prove life-threatening to many. Recent infections have posed difficult treatment challenges due in large part to resistance to current antifungal treatments.

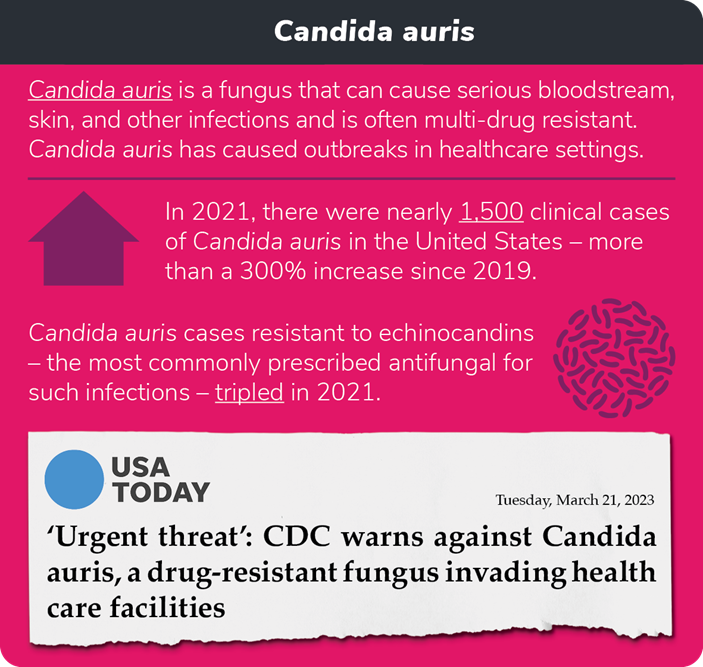

A Tragic Eyedrop Episode Sheds Light on Pseudomonas aeruginosa

One of the stranger and more terrifying instances of a superbug outbreak came to light earlier this year, after a drug-resistant strain of the bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa was discovered in over-the-counter eyedrops. That specific outbreak has infected 81 people, killing four patients and causing vision loss in at least 14 more. Four patients have had eyeballs surgically removed as a result of the infection.

That harrowing episode has certainly drawn attention. But the effects of this deadly bacteria are far wider ranging than the eyedrop incident alone. It has long been known to cause potentially fatal infections in the blood and lungs, among other places, for patients recovering from surgery. In 2017 alone, according to the CDC, Pseudomonas aeruginosa led to roughly 32,600 infections and an estimated 2,700 deaths.

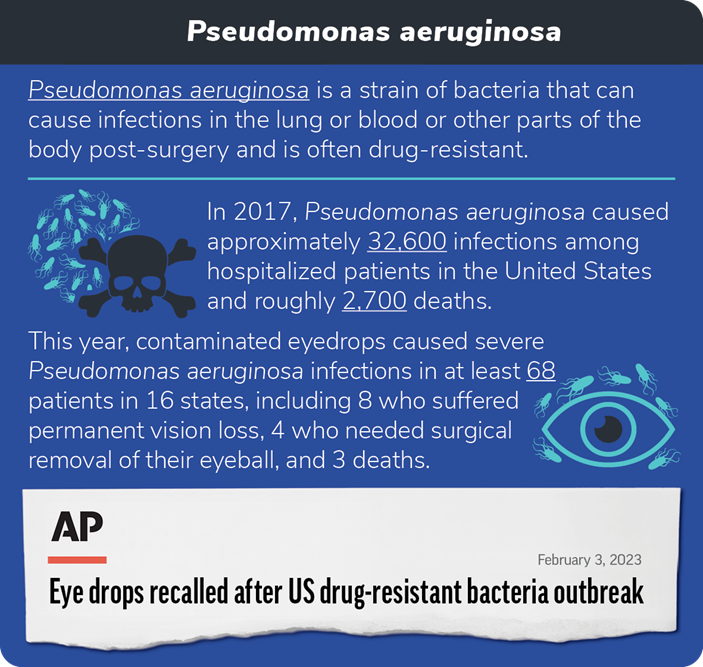

Shigella‘s Relentless Advance

This March, the CDC officially sounded the alarm about an extensively drug-resistant form of the bacteria Shigella. The infection caused by Shigella, which is known as shigellosis, affects the intestines, often leading to diarrhea (including bloody diarrhea), severe stomach pain, fever, nausea, and vomiting. It’s also highly contagious, infecting around 450,000 people in the United States each year, roughly 6,380 of whom required hospitalization.

What makes the latest outbreak so serious is that the new form of Shigella singled out by the CDC has proven resistant to all of the antibiotics currently used to treat these infections. And the share of resistant infections among all cases of shigellosis has been growing. Whereas there were no instances of drug-resistant Shigella in 2015, by 2019, 0.4 percent of all such infections were resistant to antibiotics. Last year, that share rose to 5 percent — that’s a twelvefold increase in just 3 years — signaling that the worst is yet to come.

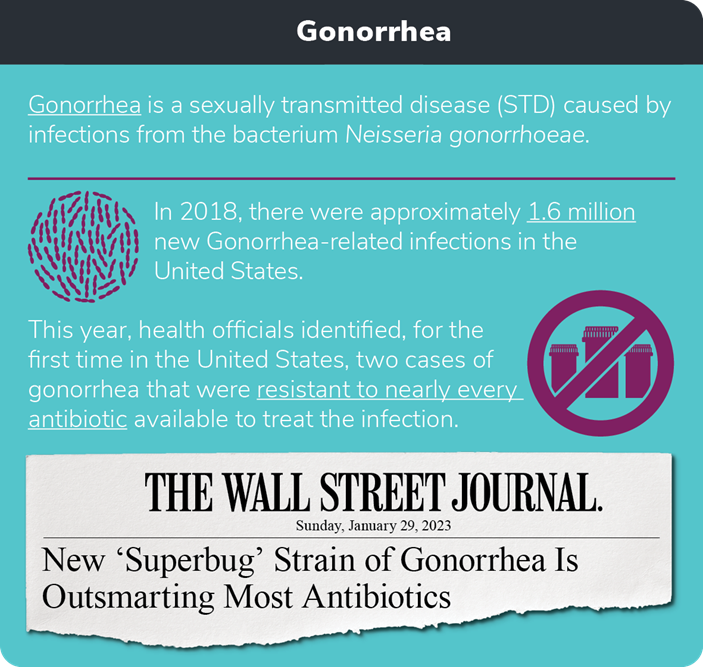

A New Gonorrhea Strain Draws Attention and Concern

Earlier this year, public health officials identified two separate cases of a new drug-resistant form of the sexually-transmitted infection Gonorrhea in Massachusetts — a discovery that soon made national headlines.

That’s because this particular strain of the infection showed either complete resistance or a reduced response to five separate classes of antibiotics. This is the first time strains of gonorrhea this resistant to antibiotics have been identified in the United States. As the Massachusetts Department of Public Health put it in response to this latest discovery, “…these cases are an important reminder that strains of gonorrhea in the U.S. are becoming less responsive to a limited arsenal of antibiotics.”

The World Needs More than a ‘Limited Arsenal’ of Antibiotics

In light of these outbreaks, it’s never been more clear that the current lack of novel antibiotics is already putting lives at risk. At its core, the lack of effective antibiotics is an economic problem more than a scientific one. We know how to create new and innovative antimicrobials to address these difficult-to-treat infections. Yet because it’s important to use antibiotics appropriately — limiting their use for only when they’re needed — companies that develop them have little to no chance of recovering their upfront investment costs and remaining viable in the traditional marketplace.

This unfortunate feature of the antibiotics market has led to a years-long slowdown in innovation. Over the past decade or so, only a handful of new antibiotics have earned approval from the Food and Drug Administration. What’s more, a significant number of companies that have attempted to overcome the economic impediments to antibiotic innovation have gone out of business in the process.

Fostering a new — and critically needed — era of antibiotic production demands reforms to incentivize this vital work. The bipartisan PASTEUR Act would do exactly that.

The legislation moves away from the current sales-based payment model, in which drug makers are paid by pill or dose. The PASTEUR Act would create a subscription-like model where contracts between the federal government and developers of novel antimicrobials would create an avenue for installment payments in exchange for access to developers’ drugs. In so doing, the policy enables companies that develop successful antibiotics to earn back their investment regardless of how frequently their products are actually used.

This policy shift would help draw biopharmaceutical startups and pharmaceutical developers back into antimicrobial research by ensuring an adequate return for developing the breakthroughs needed to bring the AMR crisis to an end.

But lawmakers have no time to lose. Without the PASTEUR Act, superbug outbreaks of the sort we are seeing today will grow increasingly common — and the tools needed to treat these conditions will remain out of reach.

Click here to subscribe to the Superbug Bulletin.