Issue No. 23: A Broken Antimicrobials Marketplace

Antibiotic-resistant “superbug” infections were involved in the deaths of nearly 5 million people across the globe in 2019. That same year, antimicrobial-resistant infections contributed to nearly 173,000 deaths in the United States alone — making superbugs the third leading cause of death from disease in America behind heart disease and cancer. And by all accounts, the global health emergency of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is worsening rapidly. A 2016 analysis projects that, by 2050, AMR fatalities could reach 10 million each year — roughly the same number of people who die worldwide from some form of cancer.

This global health emergency is all the more dire because of a decades-long slowdown in antimicrobial development. A continued supply of new and novel antimicrobials is essential to fighting superbugs. Yet, at a time when a wide array of bacteria and fungi are growing more and more resistant to existing medicines, the development pipeline for antimicrobials has slowed to a trickle.

This hasn’t been for lack of trying. Over the past few years, many biopharmaceutical companies have worked hard to create the kinds of antimicrobial medicines required to combat superbug threats. Unfortunately, the misaligned incentives within the antimicrobials marketplace have made it immensely challenging for these innovators to succeed, or even remain viable.

The good news is that, given a fighting chance, researchers remain eager to overcome the barriers that have impeded antimicrobial development for so long. What’s needed are targeted policy reforms to stabilize and sustain the antimicrobials ecosystem. By enacting these policies now, lawmakers can lay the groundwork for a new era in antimicrobial innovation to ensure clinicians and patients have the drugs they need to catch up — and keep up — with resistant infections.

The Market Failure at the Center of the AMR Crisis

Scientists have long understood the need to use antimicrobials appropriately. Bacteria and fungi are living organisms that adapt and evolve over time. Every use of an antimicrobial can contribute to resistance, making dangerous microbes unable to respond to existing antimicrobial therapies. This reality became apparent not long after the discovery of the first antimicrobials, and it’s why we need continued innovation in the sector. Furthermore, this characteristic, which is unique among antimicrobial medications, is one of the primary reasons that makes the economics of developing and commercializing new antimicrobials so challenging.

Simply put, companies engaged in R&D of novel antimicrobials must invest immense financial resources in creating products that should be used — that is, sold — only when needed. This limits the opportunity for companies to earn back the costly investments in research and development through standard volume-based sales models. As a result of this broken marketplace, antimicrobial development has fallen dramatically in recent years despite growing awareness of the looming AMR crisis.

Whereas 18 major biopharmaceutical companies were pursuing new antibiotics as recently as the 1980s, by 2019 that number had fallen to just 3. The number of new antibiotics available to patients has dwindled accordingly — at precisely the moment medicines are needed more than ever. Since 2010, in fact, only 17 new systemic antibiotics have earned Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval.

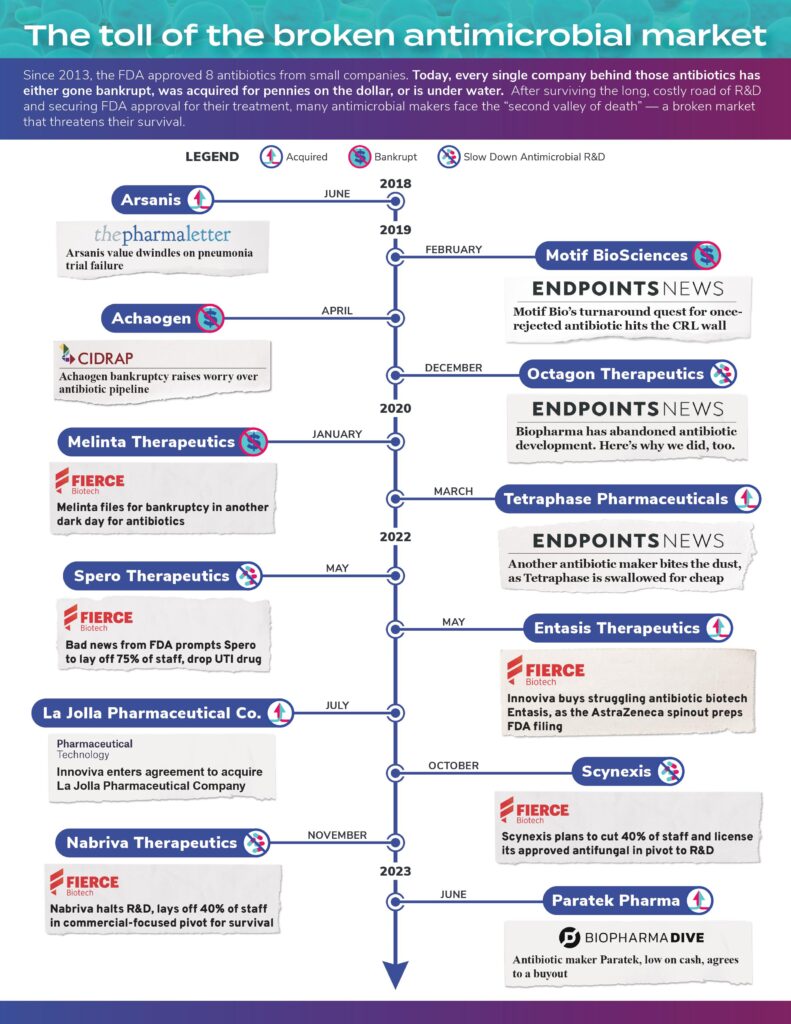

Today, companies that continue to work on antimicrobials are mostly small biotech start-ups. But these businesses face the same challenging pressures of the broken marketplace, which has resulted in the bankruptcies of several small companies in recent years, and has put others on similar trajectories.

Antimicrobials Developers Face Long Odds from the Start

The economics of antimicrobial development isn’t just challenging, but often prohibitive.

In order to bring any drug to market, companies have to overcome the so-called “valley of death” between when a medicine shows promise in the laboratory and makes it through clinical trials — where 90% of drug candidates fail. This process can take up to 15 years and requires upwards of $1 billion in funding, meaning biotech companies frequently go bankrupt.

But antimicrobial developers also face a unique “second valley of death” — which occurs after the FDA approval of a novel therapy. Because new antimicrobials are meant to be used sparingly, these companies are generally unable to recoup their upfront investment through traditional, volume-based sales. Additionally, the reimbursement structure for antimicrobials frequently disincentivizes hospitals from giving physicians access to newer treatments.

As a result, many companies that have tried to beat the odds have either gone out of business — sometimes after successful FDA approval of a new product — pivoted away from their antimicrobial R&D projects, or been acquired for pennies on the dollar. The infographic below outlines the stories of several companies — click to open it in a new tab and interact with the articles.

In these cases, most of the companies had already succeeded in creating innovative new medicines that provide additional treatment options for patients. Yet, the broken ecosystem for antimicrobials did not make it possible for these companies to stay in business.

The marketplace failure for these scientific success stories bodes ill for current innovation, for the future, and, most importantly, for patients. Right now, scientists around the world are uncovering new ways of fighting drug-resistant superbugs.

But as long as the marketplace for therapies and treatments to fight superbugs remains dysfunctional, many of these innovations will never reach patients. And the death toll from drug-resistant superbugs will continue to increase dramatically.

Improved Approaches to Address the Antimicrobial Marketplace Exist

This much is clear: If the current marketplace can’t support promising and novel breakthroughs to combat AMR due to the unique way that these products are used, then the way forward is to realign the incentives surrounding antimicrobial innovation. To that end, policymakers have worthwhile strategies available.

One promising approach is under consideration by the U.S. Congress in the bipartisan, bicameral PASTEUR (Pioneering Antimicrobial Subscriptions to End Upsurging Resistance) Act, which lawmakers reintroduced in April of last year. The legislation would create a novel payment model for new antimicrobials while supporting the pillars of antimicrobial use. The federal government would contract with drug developers for a reliable supply of novel antimicrobials, with payments that are decoupled from the volume of antimicrobials used. Doing so would provide a predictable way for companies to generate a return on investment on therapies that meet the most urgent resistance threats, incentivizing the development of novel antimicrobials based upon the value they provide for public health.

The reform created by the PASTEUR Act would go a long way toward fixing some of the structural flaws currently holding back innovation. PASTEUR would create an avenue for companies that develop urgently needed antimicrobials to remain financially viable in cases where the sales volume is appropriately low due to antimicrobial stewardship. More than that, the PASTEUR Act would encourage a new generation of antimicrobial start-ups to enter the market. This would increase the number of breakthroughs to fight superbugs and bring urgently needed new treatment options to patients in years ahead.

The UK has already implemented a similar strategy. In 2022, the country launched a pilot program where the National Health Service paid two biopharmaceutical developers a flat annual rate for access to one of their antimicrobials, in an effort to incentivize research and development in the field. Just one year later, the program’s success led the UK to finalize an expanded version of this payment model for other companies to enter into similar contracts.

Canada is also working to introduce a program that would incentivize the development of new antibiotics by providing minimum guaranteed revenue to successful developers.

Other strategies could complement critical “pull incentive” models, including antimicrobial reimbursement reforms which modify payments to hospitals to improve patient access to novel antimicrobials.

Though pull incentives are a new piece of the solution that are crucial now, “push incentives” for the development of new antimicrobials remain critical. These approaches provide direct funding and other financial support to encourage antimicrobial R&D. In so doing, these “push” incentives lower the investment requirements for this vital work, de-risking the R&D process, and spurring more and better research. Public private partnerships, such as the non-profit partnership CARB-X, are essential to providing developers the early funding boost they need to get their product off the ground, and pull incentives are essential to sustain these products once they cross the FDA finish line.

The World Can Wait No Longer for an Antimicrobial Ecosystem Fix

As the COVID-19 pandemic made clear, the scientific community is more than capable of rapidly responding to pressing global health challenges. In the case of the AMR crisis, a fundamentally flawed antimicrobials marketplace has made such a response impossible. Reintroducing PASTEUR was a critical step. Now, lawmakers must urgently pass the legislation to address these unique challenges in the antimicrobial ecosystem, or the dangers posed by drug-resistant superbugs will only grow more severe.

Click here to subscribe to the Superbug Bulletin.